The Year My Tree Died

It stood rustling its tiny red berries and pea-green leaves in the northwestern corner of our yard. The Japanese Pepper was my tree.

Sure, it cast enough shade over that portion of the garden that my eldest brother had at some point decided it would make a perfect spot for outdoor lunches and drinks at dusk. He’d arranged a hodge-podge of wooden benches in a rough circle, paint peeling, guaranteed to deposit splinters into bare summer legs. Every Friday for many years a congress of students and new migrants would occupy those benches, their voices rising into the branches of the tree as stories of homes left behind enveloped us all.

Sure, it was the bane of my mother’s gardening existence, casting so much shade that nothing could grow beneath it.

Sure, my sister and brother cursed it for dropping leaves and berries in such abundance that raking was a daily chore.

But it was my tree. My sanctuary at the end of each school day, I’d clamber up its broad trunk, scraping away peeling scabs of bark to loose colonies of ants upon the world. Perched high in its limbs, hidden by thick folliage, I’d survey the surrounds. From my lofty perch I could see the end of the dusty laneway where Anthony Perrin’s house was on one side, and where Non and Dor lived on another. I could see Old Harry’s back yard and up the concrete steps to his back door. I could see the roof of our house, where the TV antenna leaned like a rakishly worn Fedora. That tree knew my secrets, my woes and my joys. But my love for it could not protect it from what was to come.

One day, when I was 12 or maybe 13, my father decided that the tree had to come down. Or perhaps my mother decided and convinced my father that it was his idea. At 12 I wasn’t privy to the machinations of adults. All I knew was that a posse had been gathered on a balmy summer Saturday, a collection of the regular weekend visitors armed with a hired chainsaw and intent on arborcide. The tree was going down.

I took to my bedroom, wailing my anguish into my pillow as the spine-chilling whine of the chainsaw filled my ears. There’s a distinctive sound as chainsaw blades meet thick woody trunk; a muting, a resistance, a final protest. I burried my face further into the soft folds of pillow, folded the sides over my ears to block out the screams of metal and machinery.

But the screams were not metallic. They were human.

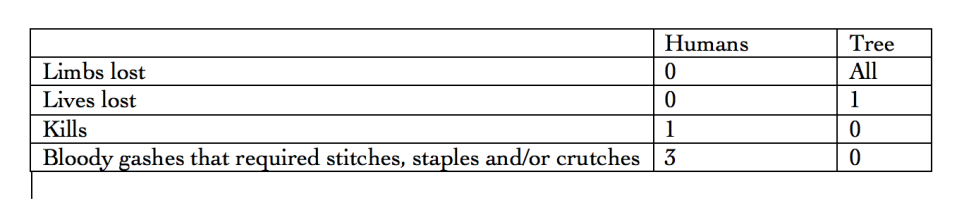

The tree was not giving up without a fight. Or the incompetence of novice tree surgeons was going to kill someone. I preferred then, and still do today, to believe the tree was making its last stand. On that day, the tree’s last, three people were sent to the Emergency Department of the local hospital with chainsaw wounds. The stats looked like this:

It was ultimately a loss for the tree, but it did not go gentle into that good night.

This post was entered in YeahWrite NonFiction #373 Challenge. Click the badge to read other entries. Don’t forget to comment and vote for your favourite.

Image credit: By Didier Descouens – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7801853

So touching Asha. It was your tree

It was! Though I’m sure my family would disagree.

You take care Asha

Ah, the tree gives fight in the form of gashes that require stitches. Loved the ending of this piece especially, Asha.

Thanks, Sara! The tree did eventually come out, but it put up a good fight first.

Your voice in this is pitch perfect. There’s a hint of nostalgia, a hint of sorrow, a hint of the girl who sat in the tree, and a whole lot of admiration for your leafy friend. I could be a bit biased though…I HATE cutting down or digging up living plants.

I knooooooow! I’m still terrible at pruning and will apologise to trees first, but they need the haircut!

Lovely, Asha! I love the personification of this old friend and the obvious affection you felt for the tree. The table at the end keeping score lent a touch of humor to your tragedy.

Ah, thank you! I’m so pleased you saw the humour in it. I do chuckle at my 12 year-old self now. That tree was definitely rotting (there were colonies of ants just under the bark!) and needed to be removed. But a heart wants what a heart wants.

A tree is life, and yes this tree had become a part of your life!! And your anecdote speaks volumes about your feelings towards it

Thanks, Ramya